ټول حقوق د منډيګک بنسټ سره محفوظ دي

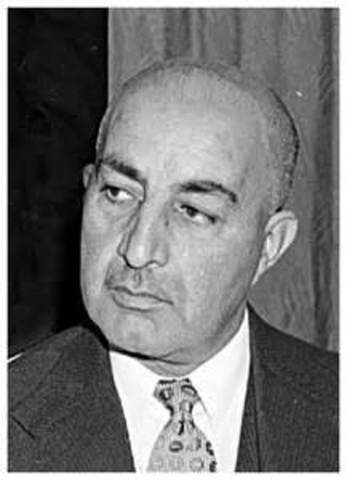

On July 17, 1973, Sardar Mohammad Daud Khan returned to power after leading a bloodless military coup against his cousin King Zahir Shah, who was traveling in Europe. This ended the monarchy and founded the Republic of Afghanistan under President Daud. The leftists gained an upper hand when a faction of the PDPA known as Parcham (banner) led by Babrak Karmal collaborated with Daud in staging the coup. The coup came ten years after Daud was forced to resign as prime minister by Zahir Shah – or as he later claimed volunteered to step down in the interest of democratization of the government. In August 1973 the king abdicated rather than risking an all-out civil war. The forces that helped Daud overthrow the monarchy consisted of three categories of people: the young leftist officers, disillusioned former government officials, and Daud’s personal supporters inside and outside the government.

Among the above categories, the Parchami Communists, due to their close ties with the Soviet Union and influence within the armed forces, wielded significant power in the new regime and exerted influence over Daud’s policy decisions. They made every effort to facilitate the expansion of the relationship with the Soviet Union at the expense of the West. They also spared no efforts to target their arch-rivals, the Islamists. The government jailed many of their leaders and forced others to flee to Pakistan where they laid the foundation of the resistance against the secular republican regime in Kabul. Gulboddin Hekmatyar, Burhanuddin Rabbani, Mawlawi Yunus Khales, and Ahmad Shah Massoud were among the leading figures of Islamists in exile. Just two months after the coup, former Prime Minister of Afghanistan, Mohammad Hashim Maiwandwal was accused of plotting a coup and he was arrested with a number of other nationalists. Following a staged investigation, the regime announced that Maiwandwal had committed suicide in jail before his trial, but it was widely believed and supported by a great deal of evidence that he was tortured to death. Certain observers believe that the plot was engineered more by the leftist intelligence and police officers than Daud himself.[1] Several independence investigative studies have been done inside and out ide the country which points to fallacy of the accusations that led to brutal punishment of the suspects.

With the return of Sardar Daud Kahn to power, the issue of Pashtunistan again found its place on the front burner of the Afghan foreign policy. Daud had tacitly blamed the monarchy for not seizing the opportunity to exploit Pakistan’s political and military weakness after its loss of East Pakistan in 1971 to get a favorable deal with Islamabad on the frontier. The leftist elements in the new regime, with the implicit approval of Moscow (to increase Kabul’s dependence on USSR) pushed the Pashtunistan issue even further at a time Pakistan was facing insurgency in Baluchistan and having been practically dismembered by the independence of Bangladesh. Afghanistan’s irredentist claims were revived causing increased wariness in Pakistan. In order to preempt Afghanistan’s efforts to support the anti-Pakistani insurgency in Baluchistan,[2] Pakistan Prime Minister Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto decided to arm the exiled anti-Daud Islamists in Pakistan to cause troubles for Daud and create spheres of influence inside Afghanistan. The Pakistani-trained and armed insurgents including the late Ahmad Shah Massoud and fighters affiliated with former Mujahedin leaders Burhanuddin Rabbani and Gulboddin Hekmatyar staged uprisings in July 1975 in the Panjsher Valley and eastern provinces which were rapidly crushed by the Afghan security forces.

This strengthened the Soviets’ hand in their effort to keep Afghanistan dependent on the Soviet Union. Their agents continuously whispered in the ears of Afghan leaders that “you have a potential enemy.” The leftists did not have to work hard since Daud himself was known to be an avid supporter of Pashtunistan. In my hour-long one-on-one meeting with President Daud in the spring of 1974, he spoke with a lot of passion about the Pashtun tribes being “under the yoke” of the Punjabi-dominated Pakistani government through “sheer use of force.” The meeting was not about the future of Pashtunistan, I was called by the Rahbar (the Leader) as he was commonly referred to, to discuss the creation of an institute, equivalent of a Defense College, to train and educate senior officials of different government departments on fundamentals of security and defense strategy in Afghanistan in order to facilitate a whole of government approach to national issues and the development of a national security culture, which the President rightfully saw missing. I was one of a number of professionals that the President had hand- picked to teach at the institute officially named the “Institute of diplomacy.” More than three years later, when I met the President in December 1977, for the last time, I found him very sober and willing to diversify the military establishment of Afghanistan through adopting suitable features and best practices of different nations. He also spoke of the wisdom of working closer with the neighbors and resolving the dispute with Pakistan.

Afghan King & Queen Visit to U.S.

Afghan King & Queen Visit to U.S.King & Queen of Afghanistan visit to the U.S. – September 1963. This is what Afghans should have status and prestigious in the world but now…Everyone is wondering what will happen next so embarrassing!Part One✔❶Like✔❷Comment✔❸Shareـــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــ#Afghanistan_history🇦🇫#mundigak_historical_society

Geplaatst door Mundigak Historical Society op Donderdag 22 augustus 2019

The shifts in Daud’s vision and his policies over some five years of his rule marked a major milestone in the recent military history of Afghanistan. They include purging the resolute leftists from the government, asserting his absolute power as legitimate President, and freeing the country from sole dependency on the Soviet Union at the expense of missing other opportunities in its international relations. The purge of selected Parchami Communists from the cabinet and other senior positions in the government began in 1975 right after the failed Pakistan-backed Islamists’ rebellion of July 22, 1975. Although the revolt was easily crushed, the leadership of the Islamist movement continued to maintain and operate bases in Pakistan and receive training at Pakistan’s special military training center in Chirat. Meanwhile, defeat of the rebellion resulted in fractures among the Pakistan-based Islamist leaders splitting the movement into a Hezb-i-Islami party under Gulboddin Hekmatyar, Mawlawi Yunus Khales and Qazi Amin Waqad; and a Jamiat-i-Islami under Burhanuddin Rabbani. The situation also led to a change in President Daud’s thoughts on Pashtunistan in support of resolving the border dispute with Pakistan.

These changes were also supported by policy shifts both in Pakistan and Afghanistan in their relation with Great Powers. Failure of the U.S.-led SEATO and CENTO pacts to extend the desired assistance to Pakistan during the war of independence of Bangladesh in 1971 (which dismembered Pakistan) drove Prime Minister Bhutto to reconsider his political and military orientation in the 1970s and pursue a balanced foreign policy including expanding bi-lateral relations with the USSR. In Afghanistan, a similar reorientation of its foreign policy was initiated by President Daud in order to balance its close ties with the Soviet Union by expanding relations with the West and reaching out to Muslim nations in the Middle East including Iran, Saudi Arabia, Iraq, Kuwait, Egypt and others for financial assistance. These events facilitated a rapprochement between Kabul and Islamabad, notably following the reciprocal visits of Bhutto and Daud to each other countries in 1976-77.

According Abdul Samad Ghaus who accompanied Daud, in his meeting in Kabul with visiting Pakistani Prime Minister Bhutto in June 1976, the Afghan leader indicated that there were countries, clearly referring to USSR, “that did not want to see the amelioration of Afghan-Pakistan relations. It was imperative that those quarters be denied the satisfaction of witnessing the worsening of relations between Afghanistan and Pakistan.”[3] After Daud’s visit in August 1976, relations between the two countries significantly improved. Transit trade moved without any hurdles and even wheat from India’s surplus crop was allowed to be transported overland from India to Afghanistan.[4] Consequently the two leaders were about to reach an agreement on the recognition of the Durand Line in return for Pakistan granting autonomy to the North West Frontier Province and Baluchistan.[5] The impending deal, however, was overtaken by events. In June 1977, a military coup in Pakistan led by General Zia-ul-Haq ended Bhutto’s government and less than a year later President Daud was murdered in a bloody Communist coup.

Daud’s weaning away from political and military dependence on the Soviet Union began in earnest in 1976. In the spring of that year, he appointed a commission of senior military professionals to review the Soviet military manuals used in the Afghan army and modify them in accordance with the operational environment and national military traditions of Afghanistan. I was appointed the head of the secretariat of the group which was presided over by General Nazir Kabir Seraj with several Afghan generals serving as members of the commission. The Commission brought together dozens of officers to work on military field manuals related to various arms and branches of service. Although the commission made no significant progress, the exercise alerted the Soviets to the possibility of Kabul parting ways with Moscow. This coincided with the Soviet mediation to reunify the two estranged factions (Khalq and Parcham) of the PDPA Communist Party of Afghanistan in the summer of 1976. This Soviet action worried Daud who “viewed its purpose as hostile to the Afghan Republic.”[6] Meanwhile, many of the Afghan elite thought that when the Soviet Union intended to invade Afghanistan it would not be through overt military aggression, but rather take place through a military coup by the Communists which would pave the way for a Soviet incursion.

The Soviet fears of Kabul drifting away from Moscow’s influence were confirmed following the stormy meeting between President Daud and General Secretary Brezhnev in Moscow in April, 1977 where Daud strongly objected to Brezhnev’s complaint about the presence of experts from NATO countries stationed in the northern parts of Afghanistan. Daud bluntly challenged the remarks of his host and, in a decisive tone, reminded him that Afghanistan was a free country and would not allow any nation, including the Soviet Union, to dictate how the country should maintain relations with other states and their advisors. “We will never allow you,” he remarked, “to dictate to us how to run our country and whom to employ in Afghanistan. How and where we employ the foreign experts will remain the exclusive prerogative of the Afghan state. Afghanistan shall remain poor, if necessary, but free in its acts and decisions.”[7] Another Afghan diplomat, Abdul Jalil Jamili, who was also present at that meeting, related the story to me in a toned-down version but essentially carrying the same message.[8] The assertive position of President Daud was apparently “the last feather that broke the horse’s back.”

On his return to Afghanistan, President Daud took concrete steps to diversify his ties with the outside world. He publicly announced that “imported ideologies,” a reference to Communism, were not what Afghanistan needed. The President signed a military cooperation treaty in Egypt and sent Afghan military and police officers for training there – a country that had adopted the same policy in 1974 to distance itself from the USSR. President Daud decided to build upon the increasing interest of the Shah of Iran in Afghanistan’s affairs to seek Iranian assistance in funding Afghanistan’s seven-year economic development plan. Signs of increased Iranian interest in Afghanistan were apparent following Mohammad Daud’s 1973 coup d’état against King Mohammad Zahir Shah. The new Afghan regime, raised fears of Moscow’s increased influence in Afghanistan at the expense of the country’s traditional neutrality. Encouraged by the United States, the Shah’s regime in Iran launched a systematic effort to offset Moscow’s influence in Afghanistan by expanding economic and political ties with Kabul.[9] Iran offered a two billion-dollar economic aid program over a ten-year period to Afghanistan. At the same time, Iran participated in channeling covert aid to underground anti-Daud Islamic groups who were fighting the Soviet influence in Afghanistan.[10] Iran’s dual track policy was aimed at blocking the expansion of the Soviet power in the region.[11] During the next few years, the Afghan government clamped down on pro-Moscow leftist elements in the administration, took steps to resolve its long-standing political dispute with Pakistan and forged closer ties with Iran and some other Islamic countries in the region.[12]

Domestically, Daud consolidated his power by adopting a new constitution that established a single party government system, the National Revolutionary Party, led by him. A Loya Jirga, whose delegates were hand-picked by the government, was convened in February 1977 and unanimously elected Daud as President for a seven-year term. Although President Daud excluded committed leftists from the new cabinet, he continued to depend on his close allies in key positions. His purge of Communists was partial, leaving many adherents of the Khalq (masses) and Parcham factions of PDPA in the armed forces. Meanwhile, disturbed by Daud’s independent policies, Moscow stepped up its interaction with Afghan Communist factions mediating their merger in July 1977- less than a year before the bloody Communist coup against the Daud regime (April 27, 1978). Thus the Parcham and Khalq factions, who were previously locked in a power struggle, were reconciled into a unified party. Even before the unification, both factions were separately planning to overthrow the government in military uprisings for which they had recruited low and mid-level officers in the army and air force.[13] The PDPA members, mainly the Khalq faction, increased their infiltration into the armed forces recruiting hundreds of Soviet-trained officers to their ranks. According to some of their leaders, the PDPA had started plotting the coup in 1976, two years before it actually took place.

In order to, distract the attention of the regime from their activities the leftists came up with a carefully-crafted deception plan. Their aim was to convince the regime that the real threat to the government was posed by the Islamist elements. The Communist operative inside the security forces even planted weapons and explosives in certain places and then tipped the government to their locations reporting that the arms belonged to the Islamist groups. This way, the leftists not only shifted the government attention from their conspiracies but also weakened their ideological enemies. Given the failed rebellion staged by Pakistan-backed Islamists in 1975, it did not take the Communist operatives a lot of effort to confuse the government and drive the security forces against the wrong targets.

(From Ali A. Jalali’s “a Military History of Afghanistan from the Great Game to the Global War on Terror, University Press of Kansas, 2017

[1] Mohammad Najim Aria, Mohammad Hashem Maiwandwal, fourth edition, Maiwand Publisher, Peshawar 1999, pp. 149-151

[2] Daud supported the insurgency in Pakistani Baluchistan, sheltering rebels and establishing training camps on Afghan territory

[3] Abdul Samad Ghaus, The Fall of Afghanistan-an Insider Account, Pergamon-Brassy’s, Washington, New York 1988, p. 127

[4] Ibid., p. 140

[5] Rubin, Fragmentation of Afghanistan, p. 100. Magnus and Naby, Afghanistan, p. 62

[6] Abdul Samad Ghaus, The Fall of Afghanistan, Perganon Brassey’s, 1988, Washington D.C., pp. 171

[7] Ibid, p. 179

[8] Author’s conversation with Ambassador Jalil Jamili in Washington 2003

[9] Diego Cordovez and Selig S. Harrison, Out of Afghanistan, Oxford University Press.1995, pp. 15-16

[10] Ibid. p 16

[11] Shahram Chubin and Sepehr Zabih, The Foreign Relations of Iran, University of California Press, 1974, pp 309-310

[12] Abdul Samad Ghaus, pp. 174-7

[13] Keshtmand, Sultan Ali, Yaddashtha-i-Siassi wa Roydadha-i-Tarikhi (Political recollections and historical events), Najib Kabir Publisher 2002, pp. 38-319