ټول حقوق د منډيګک بنسټ سره محفوظ دي

In the shimmering haze, turbans, sandalled feet and dark beards mingled with the plain dungarees of the bushmen as a crowd rushed to collect mail from the train that had just pulled in. Suddenly the hiss of steam and the excited babble were punctuated by the sound of gunshots. An Afghan fell to the ground, wounded. Another swiftly and silently slipped away into the surrounding desert. The place was Marree, South Australia; the year was 1904.

Early one hot December morning in 1986, I recalled that story as I sat under sparse shade in a dry, red-soil creek bed at Farina, 50km from Marree. Since 5am “Charlie” DadLeh and I had been on the road south from Marree to the long-forgotten site of the old Farina “Ghantown”.

As we sat in the creek bed, sipping from Charlie’s cool water-bag I tried to picture the nearby barren hillock as it had been in 1904 when occupied by tin huts, camel-yards, a simple mosque and an entire Afghan community. It was from here that Sher Khan, seeking revenge, had hidden himself on the train as it passed through on its way to Marree.

Only a few weeks before, the young cameleer had been betrothed to a girl of 14 from the Marree Ghantown. He had paid her father £100 deposit (equivalent to more than $5000 today) on the negotiated £150 bride price, and after the traditional communal feast had set off up the Birdsville Track to earn the balance. In his absence an older, wealthier Afghan made the girl’s father a higher offer, and man and girl were hastily married.

After his shooting attack on the avaricious rival, Sher Khan returned to the Farina Ghantown, where his compatriots tried to conceal him, for under their tribal code it had been his duty to avenge the deceit. But he was arrested, tried and gaoled.

Birdsville cameleer

Charlie (real name Dur Muhammad Dadleh) had been a cameleer himself, working the Birdsville Track until trucks took over. Now in his 70s, his memory was sharp with recollections of the camel days. Not for the first time, I wondered at the fortitude of Charlie and his people. Here at Farina they baked in their tin shanties in the scorching summers and were exposed to howling winds and piercing cold in winter – comfortable compared with the conditions under which they worked their cartage contracts in some of the harshest terrain in the world.

Charlie echoed my meandering thoughts: “They were real hard workers, long hours. Never took holidays in them days,” he said. Pausing, his soft, lisping voice continued: “I was out working with camels when I was 14.” And a longer pause. “I perished three times along the Birdsville Track.” My surprise turned to amusement as I realised he was using the old bush meaning of the word ‘perish’ – to become faint, dizzy, dehydrated.

Charlie had been my mentor and guide during several trips to the Marree area on my search for information about these elusive Afghan cameleers. Son of Dadleh Balooch and an Irish mother who had married at Marree, Charlie lived in Ghantown there. He had taken me to locations long forgotten by the world – old Ghantowns, lonely graveyards, crumbling old mosques. He could tell me who was buried in the unmarked graves, recall who had occupied which Ghantown hut, and vividly recount stories of the characters and incidents of childhood in Marree.

Ghantowns: part of Australia’s foundation years

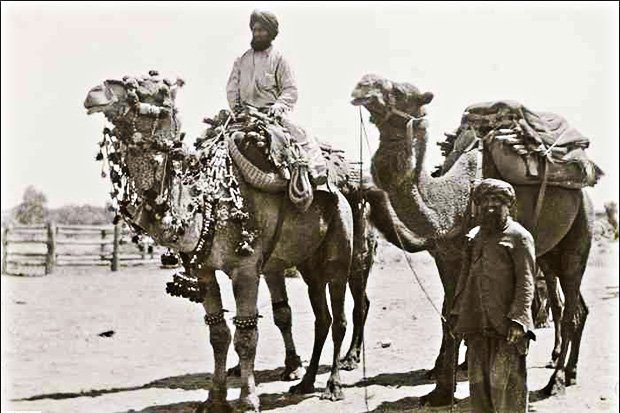

Camels opened the great central expanses of Australia. For more than 50 years until the 1920s, camel trains radiated into the outback from railways that gradually extended into the interior, or from points near otherwise isolated, inaccessible parts of the country. In long strings of up to 70, they sustained human life and new endeavours in the emerging outback communities. They carried building and railway materials, food, furniture, water, mail and medicine to the pastoralists and mining ventures, returning with the products of those inland enterprises – baled wool and oil. Camel cartage bases were formed at railheads or near ports, and ‘Afghan-towns’ developed on their outskirts. These became known as Ghantowns.

The cameleers were Muslims who adhered faithfully to their religion and built mosques wherever they settled. They brought with them no women, and although some married European or Aboriginal women, their families always lived in the Ghantowns and rarely mixed in Australian society. Camels were singularly superior to horses and bullocks in the dry centre, and the Afghan cameleers were better suited physically than the Europeans to the harsh conditions in inland Australia.

My six-year odyssey began in May 1982 at the Port Augusta wharves – where the first commercial shipment of camels and their handlers disembarked from the steamer Blackwell on New Year’s Day 1866. The shipment was made by pastoralist-entrepreneur Thomas Elder, who was determined to establish a carrying business and camel stud at his Beltana property in the nearby Flinders Ranges.

A great crowd had gathered on the wharves to watch the unloading of such strange cargo with their exotic, turbaned handlers. They weren’t, however, the first camels in Australia. Among the first were those imported in 1860 for the Burke and Wills Expedition that was the first to cross the continent from south to north. Their use on that expedition led to the later imports.

Elder’s original, elegant homestead at Beltana stood on a hill at the end of a winding road, behind date palms planted 100 years earlier by his Afghans. Station manager Peter Moroney was a little surprised by my interest in Afghans, and pointed down the hill. “They lived down there, somewhere near the troughs, but there’s only a bit of rubble left. Their cemetery was somewhere between the hills,” he said. “I’ve never been able to find it.”

Outside the homestead I passed a memorial cairn erected to the explorer Ernest Giles, who set out from Beltana station in 1875 with Beltana camels and two of Elder’s cameleers – Coogee Mahomet and Saleh – to successfully cross the Great Victoria Desert to the coast of Western Australia.

Beltana became a recruiting base for the invaluable camels and their handlers for major desert exploration expeditions – including Colonel Warburton’s horrific crossing of the Great Sandy Desert in 1873 and William Gosse’s into central Australia the same year, when Gosse and his Afghan offsider, Kamran, were the first Europeans to see and climb Uluru.

Afghan cameleer explorers

At the bottom of the hill below Beltana homestead I was surprised to see beautifully preserved stone and slate camel troughs, and the remains of a ‘camel whip’. This latter piece of Afghan ingenuity allowed water to be drawn from a deep well using two wheels, rope and bucket and two camels – one attached to each wheel. Today, a windmill pumps water to the surface at Beltana, and the water quenches the thirst of its sheep, not camels. Nearby were the crumbling stone walls of the cameleers’ living quarters, where broken china and glass, forks and a few metal fragments were all that remained of their material possessions.

Among the windswept hills I found four or five graves haphazardly huddled together. They were a dilapidated but recognisable representation of the folk graves of north-eastern Afghanistan. Some had pieces of local slate as head and foot markers; others had the wooden jenaza bier grave-surrounds (a representation of the deceased’s last bed) of the Afghan’s native land.

Faiz Mahomet was chief cameleer, or jemadar, at this first Afghan settlement in Australia. Born in Khandahar, he had come out with his younger brother, Tagh, in Elder’s’ first shipment. The brothers later became camel importers and merchants themselves, borrowing money from Elder to start their carrying business. In 1883 they established a base at the new railhead at Marree (then called Hergott Springs), which soon became the hub of camel cartage, servicing virtually the whole of central Australia.

Gold rush time

From Marree, Faiz and Tagh Mahomet and many of their compatriots followed the great 1893 gold rush to Coolgardie, Western Australia, and the new fields in the north, taking supplies to the diggers.

Coolgardie is Australia’s most famous mining ghost town. Majestic Bayley Street, wide enough for a camel-train to turn unhindered, was once lined with grand hotels (by bush standards). The Afghans lived on the western periphery. The district relied on them and their animals even for entertainment, for camel races drew the crowds. These races between locals and Afghans were the forerunners of such events as the Alice Springs Camel Cup and the Coolgardie Cup. The sight of these ungainly, exotic beasts lumbering towards the finishing line or, just as often, away from it – with their often eccentric riders, continues to give perverse pleasure to outback crowds.

Frances Tree, together with her husband is custodian of goldfield warden John Finnerty’s original house at Coolgardie. Thanks to the Trees, the house is now a public museum. “The Afghans’ mosque was on Mount Eva,” said Frances, pointing to a hillock south of the house. “The camel camp was below it, spread around the base.”

The bare, rubbly hillock was the site of the 1896 murder of Tagh Mahomet, Faiz’s brother. A Ghilzai tribesman had crept up on the Durrani merchant as he was preparing to enter the mosque for prayers and had shot him dead. It was a revenge murder: the Ghilzai and Durrani tribes had fought over leadership in their own country for hundreds of years, and factions had continued the feuding in Australia.

Their country was Afghanistan. The cameleers were indeed predominantly Afghan tribesmen – Durranis, Afridis and Baluchis (from the Afghan province of Baluchistan) – and not Indians, as some historians claim. In 1893 the Amir (king) of Afghanistan and the Government of India agreed upon a border between Afghanistan and India, and the Durand Line was drawn on the maps. But the freewheeling tribesmen paid no heed to such abstractions and straddled or crossed the line as they chose, many living at or near Peshawar (once an Afghan city) and Karachi (once an Afghan port), now both part of Pakistan.

In the coolness of late afternoon I drove to the Coolgardie cemetery, a few kilometres east of town. The Afghan graves were at the very far end. There I found the headstone that marked Tagh Mahomet’s grave, next to that of the Ghantown religious leader (mavlavha), Hadji Mullah Merban. Magenta rays from a setting sun slanted through the gums beyond, enveloping the monuments in a mystical light. As dusk fell, a vision of these men swam before me – bowing, prostrating, performing their evening prayer beside a scrubby, shallow creek or in their crude bush mosques dotted across the outback, their camels chewing contentedly nearby, the beasts’ tinkling bells barely audible above the exotic chanting.

I drove back to the Railway Lodge, one of the few hotels still surviving from the boom days that followed the arrival of the railway at Coolgardie and nearby Kalgoorlie in 1896. That significant event was followed in 1903 by the opening of a pipeline carrying water 560km from Mundaring, near Perth. The railway and pipeline ruined Afghans’ pack-camel businesses. Some took their camels north to the goldmines, around the Murchison River and into the Kimberley district; others set off for north-west Queensland. Copper mining near Cloncurry, Queensland, was booming in the late 1890s as the world price escalated.

Last century the whole area, from Bourke to Barcaldine, was ablaze with violent clashes between cameleers and the Australian horse and bullock teamsters. ‘The Great Shearers’ Strike of I891 had inflamed deep antagonisms. ‘The Pastoralists’ Union was attempting to lower both carrying charges and shearing rates because of a slump in wool prices, and its members were glad to use the cheaper non-unionist cameleers from over the border to carry baled wool from strike-bound areas. The police and army had to be called in to protect the Afghans and their camels.

An important Afghan leader in Cloncurry last century was the flamboyant esmel merchant Abdul Wade, known as the ‘Prince of the Afghans’. He arrived from Bourke, NSW, following the copper rush. The headstone of his chief cameleer Sayyed Omar, who was the Ghantown’s mullah (prayer leader), is one of the few to survive in the Afghan section of Cloncurry’s cemetery.

Settling in Alice Springs

It is ironic that although Alice Springs has been popularly and romantically linked with camels and Afghans in recent years, Alice was the last place where the cameleers settled. Their camels serviced central Australia from Marree and Oodnadatta until well after the turn of the century.

During one of several visits to Alice Springs, one of my great thrills was the sight of a herd of feral camels on the Oodnadatta Track. The track runs close to the path the Afghans took from Marree and Oodnadatta to Alice, and on my visit it was bordered by brilliant red rosy docks that are believed to have germinated from the grasses and seeds used to stuff camel saddles.

On the outskirts of Alice, I found the Mecca Date Farm, with the palms originating from eboee the Afghans planted in various Ghantowns between Marree and Alice Springs. Dates were the fruits of the Prophet, enriching the health and the spirit, and were eaten at the end of the day during Ramadan, the month-long religious fast. Jim Lukin, the farm’s Swiss-born proprietor, showed me the palms from which much of the plantation had been seeded, now named for certain old Afghan characters like Saddadeen and Abdul gbarlick.

Camel farms around Alice Springs today lead safaris on which adventurous Australians and overseas visitors, get a taste of the romantic outback. I met Robin Mcleay when I came across one of his camels tied to the branch of a tree outside a shopping complex, and visited his camp south-west of Alice Springs at the edge of the MacDonnell Ranges. From there he takes those brave enough along the craggy escarpment and into the ranges. While we were having a cup of tea, a playful young camel stole the teapot and refused to give it back.

Camels are curious, intelligent, strangely endearing animals. Today only a few second-generation descendants of the original Afghans are still alive in Australia, most being in their 70s or older. A few still live in their original Ghantown houses, with Muslim mementos of camels and turbaned men on their walls. They have a quiet dignity and reserve; their houses smell deliciously of curries, they keep the pork taboo and many remember a few phrases in Pushtu or Dati, a few prayers in Arabic.

Marree, the centre of Afghan activity in Australia has the longest-surviving Ghantown. Still living there are the descendants of Khan Zadaa, Moosha Balooch, Dadleh Balooch and Mullah Assim Khan.

Afghan influence has stretched from Perth to Townsville, from Melbourne to Port Hedland, from Adelaide to Darwin – criss-crossing inland Australia. Afghan cameleers played an extraordinarily important – and unacknowledged – part in our history.